My heart is beating fast. My eyes are flickering. My hands are clammy, and I can’t read my notes. My thoughts are racing… I can’t focus.

But this isn’t supposed to be scary, is it? I’m not performing in front of a hundred people, I’m presenting some design ideas to a handful of my close colleagues.

The Problem

Every time I plan to speak or perform in front of people, I throw up or become nauseated. It doesn’t make sense, but I do. I am an outgoing and extroverted person, with no fear when it comes to meeting new people. I am a people person that can easily whip out a joke or ask a spontaneous question in a crowded room, but if I am supposed to talk and it’s planned, my body breaks down. I can’t eat, I can’t breath.

«Every time I plan to speak or perform in front of people, I throw up or become nauseated.»

Today I work as a UX Designer, but I am also a trained firefighter. How can it be that jumping into freezing water or a burning building is no problem, but presenting my design ideas to coworkers in a meeting shuts me down? How is heading into a car wreck to help someone pinned down after a collision different than playing football (soccer) in the 6th division? How am I able to perform and put aside the obvious risk in dangerous situations, but not able to perform when presenting my design work?

This problem with public speaking, speaking in meetings, or taking tests, really sets me back in my career as a UX Designer, and in life in general. I especially struggle with interviews. Right before the interview for my current position, I threw up in bushes outside the office. I am afraid to pass this awful fear on to my kids, or to even let them see their dad this scared and vulnerable.

It is reassuring to hear that great artists like John Lennon, Eminem and Steve Jobs all have had the same reactions to performance anxiety as me. But at the same time, it is unnerving to read that none of them managed to get this under control.

Yet I still got that job, and later the interviewer mentioned that they didn’t even notice that I was nervous. Perhaps the performance anxiety helped me focus?

«His palms are sweaty, knees weak, arms are heavyThere’s vomit on his sweater already, mom’s spaghettiHe’s nervous, but on the surface he looks calm and ready...» Eminem

The Science

Performance anxiety. Fight or flight. Nervousness. Butterflies. Drymouth. The heart going at 190 beats per minute. I am not out running or exercising, but my body treats reacts in the same way. I am only presenting my design work. My brain knows the difference, but does my body?

- Jeg kan bli sittende i timesvis, banke i bordet og bli skikkelig forbanna

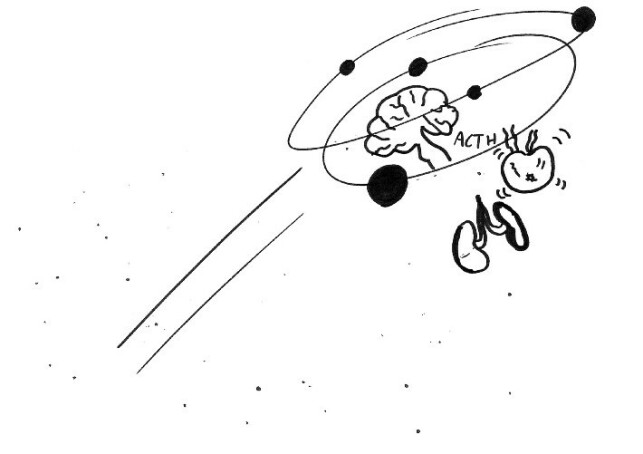

As a social species, the instinct to worry about what other people think about us is written in our DNA. This jungle code is hardwired into a primitive part of our brain, and doesn’t always translate to a modern world and our modern problems. When asked to perform your body reacts like this: Your brain (specifically, the hypothalamus) tells your pituitary gland to secrete ACTH, a hormone that instructs your adrenal glands to shoot adrenaline into your blood. Your blood pressure rises, you start sweating and your pupils dilate. Your digestive system shut down, maximising the oxygen and nutrients to muscles and vital organs. This is the fight or flight response, priming you for a quick escape.

Take food poisoning as an example. If you have ever gotten food poisoning from a specific food, your mind might connect that food with something bad. Your body will then begin to react, when you see or even just think about that specific food. This is the brain trying to save your body from dying, and it will try and prohibit you from eating what is “dangerous”.

The Solution

Though dilated pupils are great for seeing things far away clearly and planning an escape route, they are horrible when trying to read the notes in front of your face. So how do we cope with this? Fear and anxiety manifests itself differently in different people, but try and focus on what you can control. You are not at the mercy of your own emotions, you can learn to control them — or at least tame them.

- Som kvinne har det vært slitsomt å alltid måtte bevise at jeg kan det jeg driver med

Here are some of the techniques fighter pilots, top athletes and surgeons use to learn how to keep calm under stressful situations. If it is proven to help in these professions, why should it not work in yours? Remember to take small steps, and go easy. Eventually those small steps add up, and take you where you want to be.

- Practice!

Practice a lot before you are suppose to talk, or present your work. Practice in a similar environment to the one you will be presenting in. This will increase your familiarity and reduce anxiety. Practice will convince your body that this is a good thing, and not dangerous. - Trick your own brain!

Right before you are supposed to go on stage or present your work, breath deeply and raise your arms above your head. This will trick your hypothalamus into triggering a relaxation response in your body. Stage fright and performance anxiety hits hardest right before you perform, so try and do this as close to your performance as possible. This will not make you overcome stage fright or performance anxiety right away, but can help you handle it a bit better, and you can adapt to it. - Mindfulness!

Through mindfulness and yoga, you can learn to calm down on command by control your breathing and thoughts. If you are able to calm the mind when it storms at its worst, it will trigger a relaxing sensation in the body, and can help. There is a lot of help easily available for instance on your phone. Try to start every morning with 10–15 minutes of mindfulness. - Expose yourself!

Aim to hold small presentations as often as possible. Science and statistics show us that the more you expose yourself to the problem, the easier it gets to cope with the fear. For instance, for people who have a fear of dogs, that fear can often be relieved by logging a lot of positive experiences with dogs. In the beginning, just being near a friendly dog. And gradually move closer, and eventually let the dog sniff your hand. And as time goes, eventually pet the dog. This is known as exposure therapy.

I have not yet overcome my performance anxiety, but I am constantly working on adapting to it. Writing this little piece of exposure therapy has been a huge step on my journey, and I hope to be able to share a “Part 2” where I can tell you what worked for me, and why.

Thanks!

Thanks everyone who has contributed to this post, and those who pushed me to do it. Martin, Sonja, Erik and the all other wonderful people in my community of practice at work, “applied psychology and neuroscience”.

Thank you for pushing me, and your valuable feedback, input, spelling and grammar checks! Thanks!

Unnskyld, jeg skal bare jobbe litt

Slik gikk mitt første møte med åpent landskap.